Talis Putnins is a professor of finance at the University of Technology, Sydney. One of Australia's top experts on asset pricing, he recently published one of the foremost studies of the US ETF industry. The study, which he co-authored with several academics at Cornell University, argues that the vast majority of ETFs are actively managed

, and r

ather than undermining active management, ETFs are making it grow. We caught up with him below to find out more.

ETF Stream: Your new study argues that almost 90% of US ETFs incorporate some kind of active management. This is a finding that may surprise a lot of people. How do indexes and ETFs let active management slip in? Stock selection rules? Weighting rules?

Talis Putnins: It's not that most ETFs have an "active" manager in the traditional sense that is doing stock picking within the fund to try and beat a benchmark, although some do. Rather, many ETFs track increasingly specialized and niche indexes that allow an investor to get highly specialized exposures to narrow segments of the market, or specific factors. For example, we have ETFs that give an investor exposure to AI or robotics, ETFs that specialize in obesity-related stocks, ETFs tailored to Gen-Y, ETFs that give exposure to value/size/momentum factors, or factors such as low volatility, high dividend payers, and so on.

The "activeness" of ETFs plays out in two ways. The first is the design of the specialized indexes or rule-based algorithms that govern what goes into the ETF portfolio. In some cases those are active investment decisions. The second and perhaps more important way is how ETFs are used by investors. Most ETFs are not designed to be a complete portfolio for an investor, but rather, they are building blocks from which investors can create their own "active" portfolios in an efficient, low-cost manner. For example, if I have a view that robotics, platinum, small caps, and value stocks will do particularly well, ETFs allow me to easily construct a low-cost portfolio that expresses those views and will beat the market if my views are correct. That is active investing, not passive.

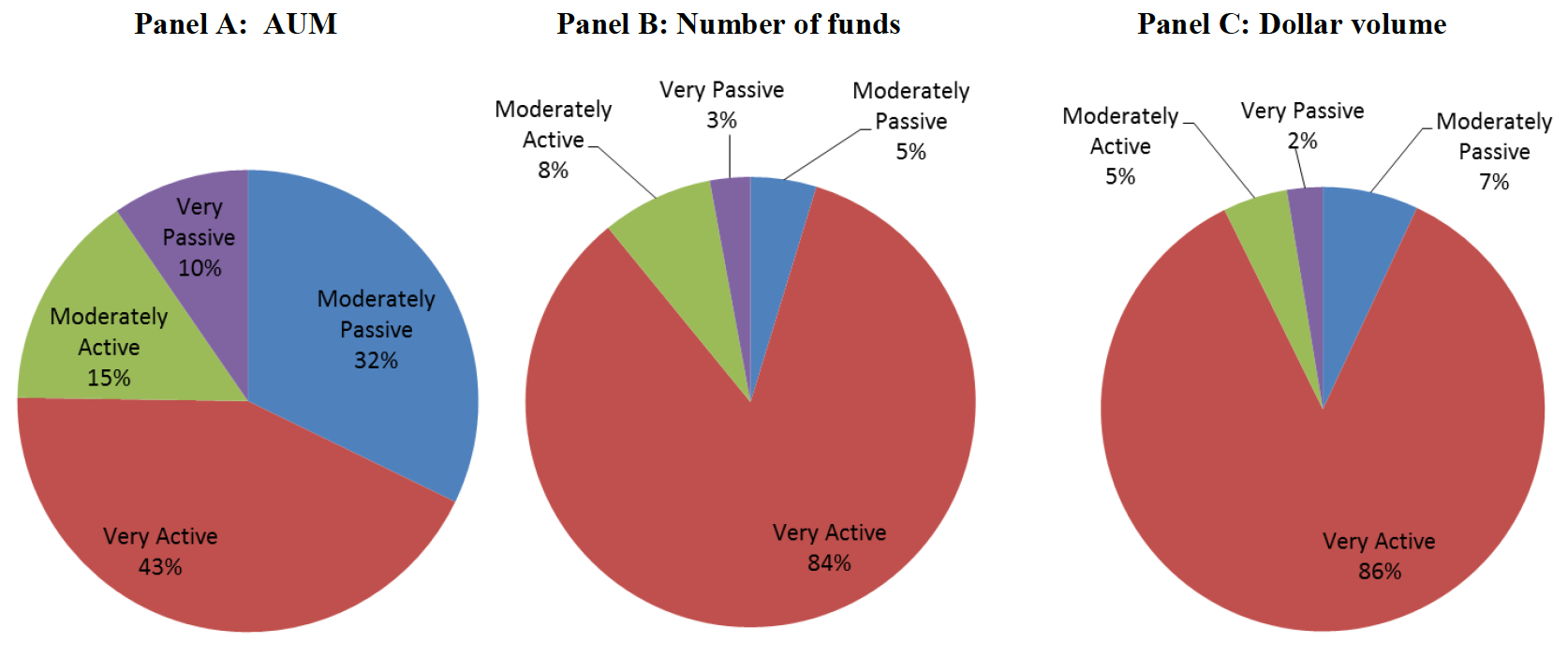

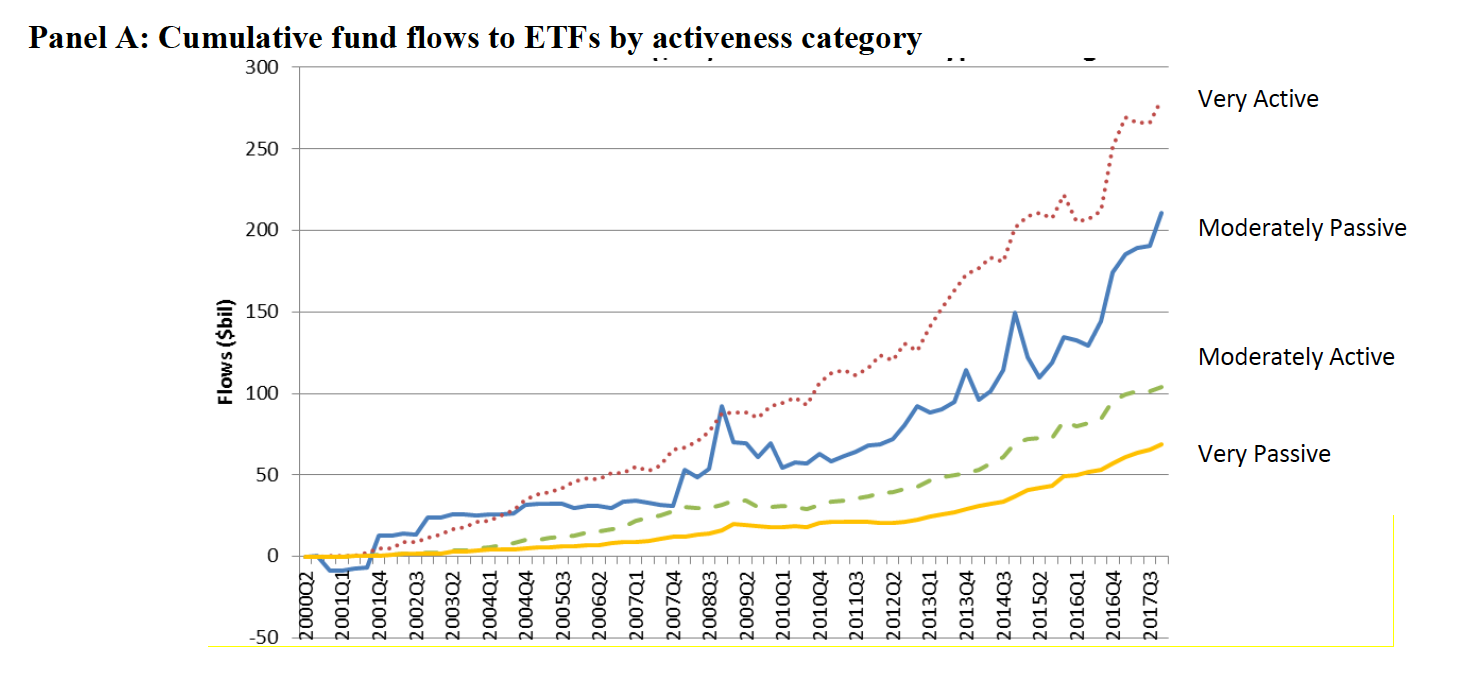

ETFs could also be used for passive investing, and some are. For example, I could invest in one of the broad market ETFs that earns close to the market return. A passive investor would use the broad market ETFs, not the highly specialized niche ETFs. Our finding that most ETFs, whether measured by number, assets (AUM), or turnover, are "active" in the sense that they depart considerably from tracking a broad market index indicates that much of the activity in ETFs is active investing. The high turnover of ETFs - a characteristic of active investing - further supports this conclusion.

What this means is that the growth of ETFs does not necessarily reflect a shift to passive investing. Rather, it reflects a change in the way active investing is done. Instead of active investing through high-cost traditional mutual funds, many investors are choosing to actively invest through ETFs. And we are not just talking retail investors here - many institutional investors are finding ETFs useful to implement their active strategies and get exposure that corresponds to their views rather than using individual stocks.

Does this mean that smart beta ETFs are essentially cheap active management?

This is how smart beta funds are viewed by some investors. Traditional active mutual funds do not have a good track record in terms of the returns they have delivered to investors. They generally underperform their benchmarks after fees. Some funds that deliver strong returns by loading on various factors that earn return premiums, such as size, value, momentum, quality, illiquidity, low volatility, and so forth. Smart beta ETFs allow investors to efficiently gain exposure to those factors in a low-cost manner. Essentially, through smart beta ETFs investors can obtain whatever factor exposures they might want but bypassing the middleman - the high-cost fund manager.

There is another use of smart beta ETFs, in particular the single factor ones, and that is factor timing. While factors have in the past delivered return premiums, they go through cycles of performing well sometimes and poorly at other times. Factor timing involves rotating through factor exposures according to one's view about which factors will perform well over the coming period. Doing so with single-factor ETFs rather than individual stocks can be easier and cheaper. There is evidence that institutional investors use single-factor ETFs in this manner, and do so successfully.

Another way that institutional investors use single-factor ETFs is to add a factor tilt or remove a factor tilt from an existing portfolio. Say a portfolio they construct is too heavily tilted to value and not enough to small caps. Single-factor ETFs provide an easy way to adjust those tilts to the desired exposures.

You dismiss the idea that ETFs are parasitic on active managers' price discovery. Could you please walk us through the evidence for why you think this is a myth?

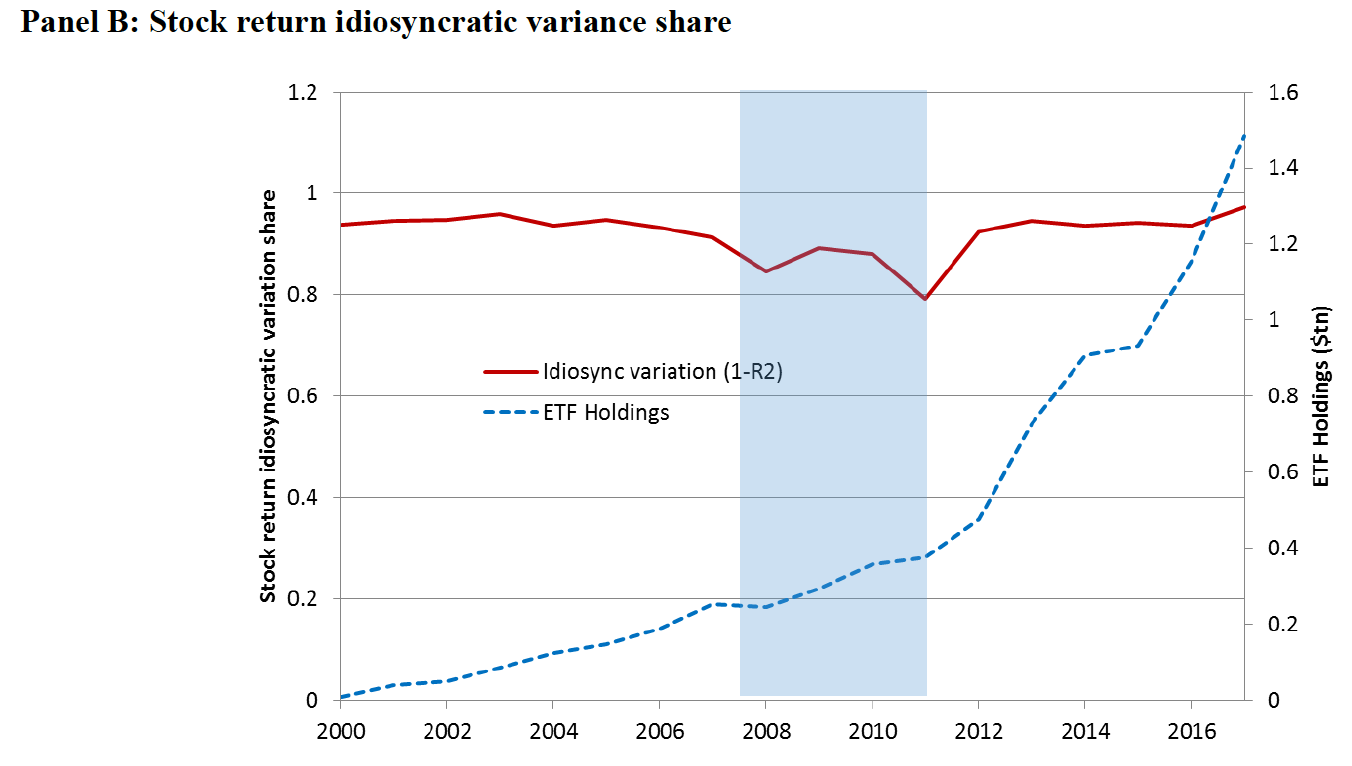

To the extent that ETFs are used in implementing active investment strategies, or as building blocks for active investment portfolios, they are likely to play a role in price discovery. Thus, ETFs do not merely feed on the price discovery of others, but they help bring information to the market. Studies provide evidence of this.

I think the comments about parasitic behavior are directed to passive investing and ETFs only get wound up in these arguments because many people incorrectly label ETFs as a whole as passive investing. If a passive investor simply invests in a broad market index without regard for absolute or relative valuations and does so in a low-cost manner without making losses to active investors, then they don't contribute to price discovery. Active investors drive price discovery.

Does this make passive investors parasitic? I don't think so. For them to be parasitic implies that in relying on the price discovery provided by active investors, passive investors harm active investors, which I don't think is the case. It seems to me this claim of parasitic behavior has been put forward by traditional active fund managers that have suffered large outflows of funds in the past decade. Those outflows, largely going to low-cost vehicles such as ETFs and index funds, mean traditional active managers make less in fees. That is where traditional managers are perceiving harm. But think for a moment who is feeding on whom? Traditional active managers feed on their investors by charging them relatively large fees. Not only do traditional active fund managers rely on these fees to survive like a parasite relies on its host, but the fees also harm the long-run performance of investors, much like a parasite harms its host organism. Fees are one of the strongest predictors of underperformance. So, if anything, the parasitic relationship is between high-fee fund managers and their investors.

What's the difference between a 'moderately active' and a 'moderately passive' ETF, as you define it?

Simply the extent to which the ETF's holdings differ from the broad market index. An ETF in our "very passive" category holds a portfolio that is very similar to the value-weighted market portfolio. "Moderately passive" ETFs somewhat depart from the market portfolio, for example they might focus on large stocks, but are still fairly broad in their holdings. "Moderately active" ETFs are already narrow enough that we would not consider them passive investments. And finally, "Very active" ETFs are highly specialized and have concentrated holdings - they are used for specific bets on a group of stocks, a segment, or a narrow factor.

You also note that the proliferation of ETFs doesn't necessarily mean that passive investing is getting more popular. Why do you think people find active management so appealing despite knowing that actively managed funds, on aggregate, must equal the market?

My personal view is that many people, in particular those managing money, are not willing to accept an "average" outcome up front, which is what passive investing offers. Many people want to be better than average, which is what leads them to active investing. This is partly driven by overconfidence and over-optimism, leading to the belief of being able to beat the average. Many studies show that we think that we are better than we in fact are.

Even though many investors recognize the basic arithmetic of investing, namely that the active investors as a group will earn close to the market return before fees, most believe that they are better than the average investor and therefore are likely to outperform others. A further contributor is the lack of financial literacy among retail investors. Many are not aware of the evidence on active fund manager performance or the fact that fees are a strong predictor of the degree of long-run underperformance.

Do you think a better distinction than active vs. passive is judgement vs. rules-based?

I don't think so. I think there is still an important distinction to be made between active and passive. In making that distinction, we just have to be careful to not incorrectly attribute certain investments to passive that are actually forms of active investing, such as many of the ETFs that exist today, particularly if they are used in an active way to make bets in the market. Judgement and rules-based can both be forms of active investment. When it comes to ETFs, the two are often used together. For example, it is common to apply judgement to pick the rule-based vehicles that one believes will outperform. This is how ETFs are used in active investing.

If ETFs lower the costs of active management, does that raise the chances of beating the index? After all, a big part of the reason active managers lose to passive is their fees.

I think it certainly raises the chances that the ultimate end investors will walk away with better investment outcomes - higher long-term returns, not necessarily because they are beating the market through active investment decisions, but simply because they will lose less of their wealth in fees.

I don't think that having lower cost investment vehicles such as ETFs will necessarily make it easier to beat the market - as it becomes cheaper for active investors to implement their strategies through ETFs, we could see more active investing, ultimately making the market more efficient. There is some evidence to that effect. In other words, the efficiency of ETFs as a means of implementing active strategies could have a flow on effect and make the market more efficient overall. ETFs can also help markets become more efficient by relaxing some of the constraints or frictions that exist in markets. For example, through their stock lending activities, ETFs relax short selling constraints in hard-to-short stocks, which can help correct mispricing in such stocks. ETFs are also useful for hedging. For example, by shorting an industry ETF industry risk can be hedged while taking an active position in an individual stock.

This is not to say that there aren't any distortions created by ETFs. In particular, as some ETFs become very large, they carry a lot of weight in the market and large flows in or out of these funds, or rebalancing events, could potentially have significant price effects.