Yao Zeng is an assistant professor of finance at the University of Washington (he will be moving to Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, in July). He is one of the world’s foremost experts on bond ETF trading and his bond ETF research has been cited by regulators and academics around the world. Following the discounts bond ETFs blew out on in March, we asked Zeng for his thoughts on the subject.

ETF Stream: Bond ETFs around the world blew out on discounts when coronavirus panic hit in March. Some junk bond ETFs had discounts as large as -25% during their peak. Many investment grade corporate bond ETFs had discounts above -7%. Were you surprised by what happened in the bond ETF market in March?

Yao Zeng: No, I was not surprised. We had the ETF "flash crash" back in 2015 when some equity ETFs traded on even larger discounts.

If anything, this March was actually less mysterious as many investors expected the bond market to be strained for macroeconomic reasons. And as it is easier to trade ETFs than the underlying bonds, we unsurprisingly saw a huge volume of bond ETFs being dumped.

Do you think the bond ETF discounts were a problem?

It’s hard to say.

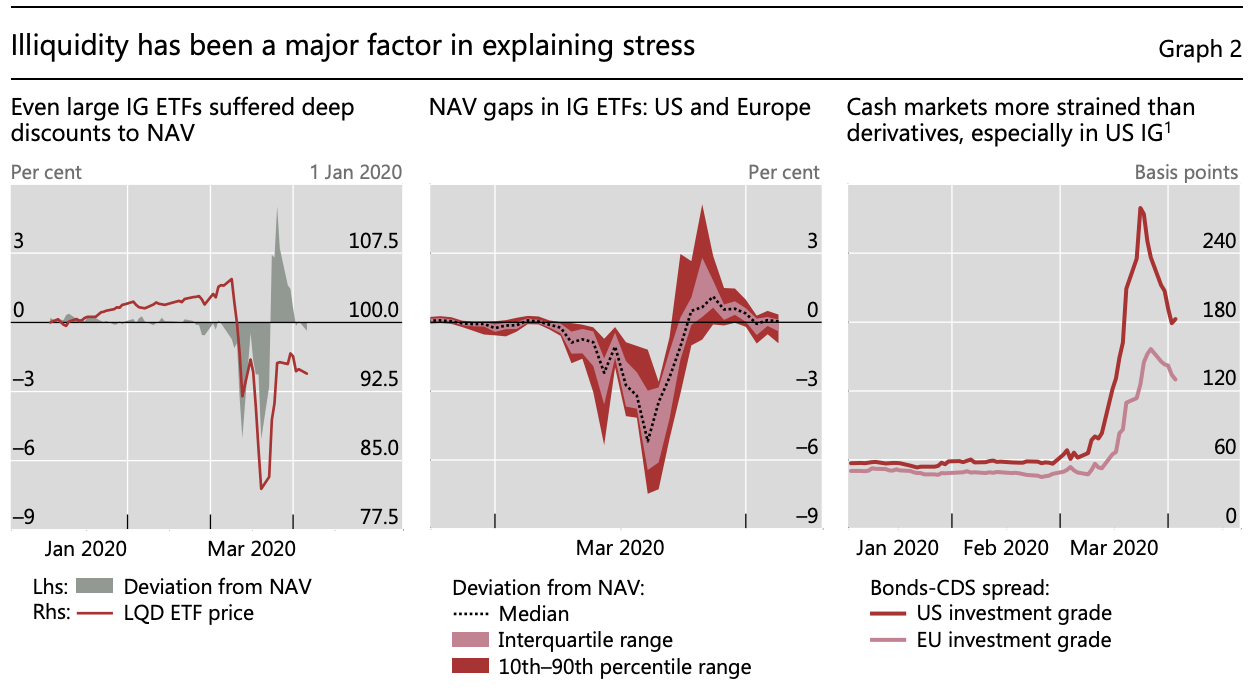

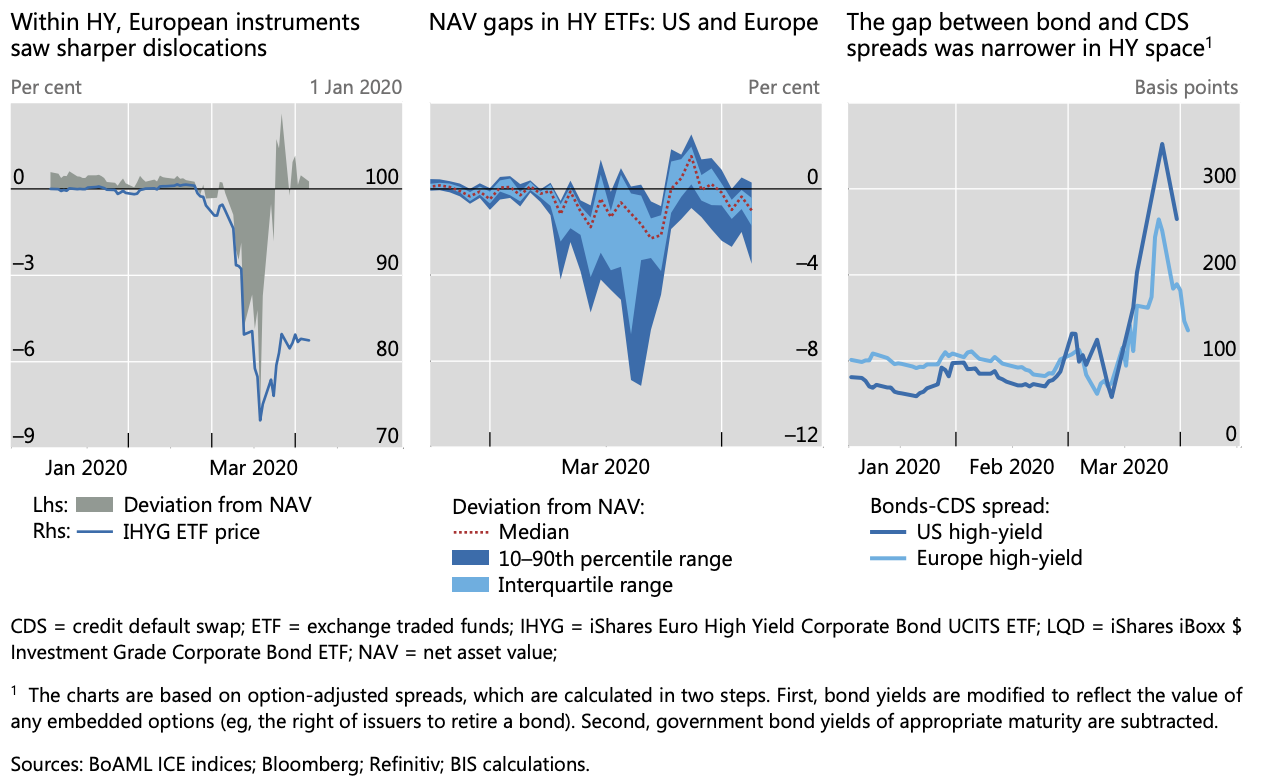

On the one hand, no – they were not a problem. The discounts were short-lived. They disappeared right after the Federal Reserve announced its intention to buy fixed income ETFs directly. Also, although those discounts were upsetting for some, they imposed no systemic risk.

Source: Bank of International Settlements

However, discounts also suggest a lack of arbitrage by authorised participants (APs) – which are the investment banks that also control most bond trading.

Without efficient AP arbitrage, ETFs essentially go back to being closed-end funds, and we do not like closed-end funds exactly because they are often traded at large discounts. And I guess the kicker is nobody knows how persistent those discounts would have been had the Fed not intervened.

Some have suggested that bond ETF NAVs and indexes were partly to blame for the discounts. They said that bond ETF discounts provide a leading indicator of what bonds are worth, as bond ETFs trade more frequently than the bonds they hold. Do you think bond indexes and NAVs are partly to blame for discounts?

Bonds are subject to stale pricing issues, undoubtedly. As a result, ETF NAVs are slow-moving, and NAVs may be “wrong” in the sense that they do not reflect the real-time bond values. So yes – discounts may indeed come from incorrect NAVs.

But it does not logically follow from the NAV being “wrong” that the ETF prices are therefore “right”. On the one hand, because ETFs are easier to trade, they may aggregate information more efficiently and help with price discovery.

On the other hand, and by the same token, the very fact that they are easier to trade may make ETFs attract a lot of so-called “noise” traders who simply panic or herd.

Source: Bank of International Settlements

In March, it is possible that the latter force dominated. There were clear signs that the market was overshooting at the onset of the coronavirus outbreak, and many investors were simply following sentiment. So, it is hard to tell whether ETF prices or NAVs are more to blame for the discounts.

But even if the price discovery role dominates, we still need a well-functioning AP arbitrage mechanism to pass the price discovery benefits of ETFs to the underlying bonds.

Without AP arbitrage, we can never be sure whether buying ETFs truly means tracking the underlying bonds or anything at all. In other words, ETF prices may be “right”, but right about what?

Bond ETFs only make up a tiny fraction of the overall bond market. Are bond ETFs being used by the banks to price the far larger bond market? And if so, is there a possibility that ETFs can affect the OTC bond market?

First, although bond ETFs only hold a tiny fraction of the overall bond market, their AP arbitrage activities actually account for a much larger proportion of the total daily bond market trading volume. So it is misleading to just look at things on an AUM basis.

I am not personally aware of any evidence of banks using ETF prices to price bonds, although it is very common for large institutional investors, including some banks, to use bond ETFs to help with liquidity management.

There is a separate academic debate about whether ETFs make the underlying bond markets more liquid. It is definitely possible that ETFs affect the bond market, but whether the effect is good or bad is a very hard question.

Some argued that bond discounts owed by bond ETFs acting as a "release valve". They claimed that had bond ETFs not existed, fund managers would have had to sell even more bonds, causing worse carnage. It's a counterfactual argument, but what's your reading on it?

This is related to the last two questions. Had bond ETFs not existed, money managers might have indeed sold bonds directly and made things worse – sure. But at the same time, there might have been less noise trading in bonds compared to ETFs because bonds are so hard to sell.

So it is ultimately a data question. But as you pointed out, we simply do not have a counterfactual to answer it definitively.

One of your areas of research has been the conflicts of interest that APs have. On the one hand, they have an interest as ETF arbitrageurs to keep ETFs tightly priced. But on the other hand, they also deal their own inventory. Could you please walk us through your findings?

Yes, the corporate bond ETF market is a bit different to other kinds of ETFs. Corporate bond trading is centred around a small group of investment banking titans whose balance sheets essentially run the show. The banks have a dual role: they are the APs for corporate bond ETFs, but they also trade their own inventory for a profit.

My research found that a conflict can arise between the banks' dual roles because both roles require access to the banks’ balance sheets. This problem has become more acute thanks to Dodd-Frank and the Volcker rule, which were introduced after the 2008 financial crisis.

When the banks’ balance sheets are constrained, they can withdraw from ETF arbitrage. But worse, because ETFs are easier to trade than bonds, APs may even create ETFs for the purpose of managing their illiquid corporate bond inventory rather than for closing the price gaps between the ETF and bond markets, thus further distorting ETF arbitrage and leading to even larger price gaps.

I think what happened in March may have partly reflected this conflict of interest.

What do you make of the Fed’s intervention?

It is smart for the Fed to buy bond ETFs today to help ease the credit conditions for corporations.

The banks have been increasingly reluctant to use their balance sheet to hold bond inventories. The problem has become worse recently as bank inventories have been stretched from 2018 onwards by the need to absorb new Treasury issuance.

When the Fed buys ETFs, an easy solve presents itself and the banks are given a workaround to Dodd-Frank and the Volcker rule. How?

Because when the Fed announced its ETF and bond buying program, it helped close the ETF discounts (or even made them trade on premiums). This then gives the banks an easier arbitrage trade: they only have to buy and redeem fewer ETFs and accumulate fewer bonds on their balance sheet. Knowing they have the Fed as a bond buyer further frees the banks from worrying about their own balance sheets and ensures the banks buy corporate bonds.

[Clarification: the Fed has announced that it will not purchase ETFs that trade on significant premiums.]

It does pose other issues though. People may now worry about ETFs becoming the next too-big-to-fail thing. And if the Fed can buy bond ETFs, will they next buy stocks or equity ETFs like the Bank of Japan? But those are different stories. Probably only the coronavirus itself can tell.

Sign up to ETF Stream’s weekly email here