In his latest annual letter, Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett complained that his firm’s enormous size meant that there “remain only a handful of companies in this country capable of truly moving the needle at Berkshire”.

As it struggles to find purchases at attractive valuations, the firm’s cash hoard has jumped to a record $167.6bn, according to data from Bloomberg.

In America at least, large, listed companies have become relatively expensive and the winners relatively undiversified.

As the S&P 500 index of leading US listed companies powered through the first quarter of 2024, concerns grew over the domination of the large firms driving the rally.

Then in April, the market adjusted down as Facebook-owner Meta announced lower-than-expected earnings and US inflation proved more persistent than anticipated.

In theory, this should have seen large caps lead the declines but in reality, the imbalance towards the mega-caps tilted even further in their favour.

Furthermore, market history suggests that a stronger US economy and accompanying higher long-term interest rates should be buoying up those smaller and more sprightly companies that are more sensitive to economic growth. But that is not happening.

Given the massive gains posted by US large caps, now is surely a good time for investors to consider whether larger companies could continue to enjoy their dominant position and whether small caps actually stand a chance of breaking through anytime soon.

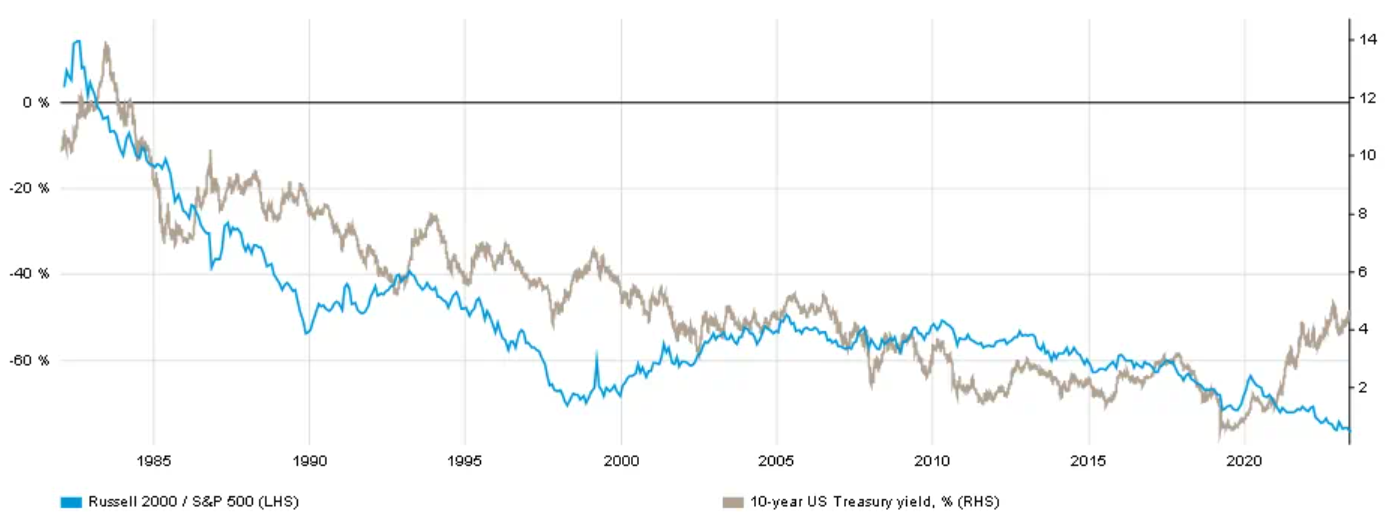

Chart 1: Small caps underperform large caps as bond yields rise

Source: RIMES, Thomson Reuters

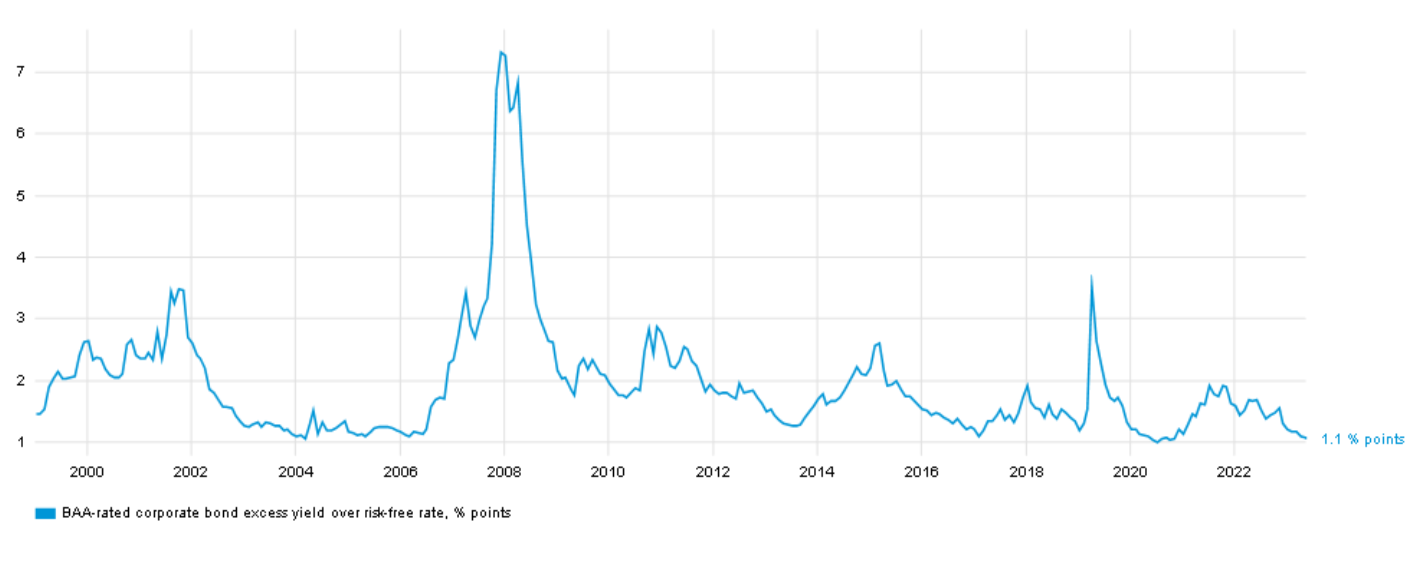

Corporate borrowing costs

At heart is the issue of interest rate movements and how different market segments react to them.

Higher interest rates have a different effect on smaller companies’ valuations versus larger firms due to their different sources of financing.

Large corporations in America have tended to be shielded from higher rates due to the unique role the corporate bond – credit – markets play in providing cost-effective financing for long periods of time.

In particular, a lot of cheap debt was taken out during the pandemic which has led many commentators to talk of an imminent ‘maturity cliff’ when the debt would come due and only higher rates would then be available for large corporations.

This would tie in with the experience of many homeowners on both sides of the Atlantic who enjoyed low fixed rates for many years, until the reality of refinancing at higher rates from 2023 onwards started to become apparent.

Except in the case of large US firms, they have had a reprieve because those significantly higher rates never really materialised.

High-quality investment grade companies can go to the credit markets today and borrow at just 1.1% more than the risk-free rate that the US government itself enjoys access to.

Compare this with the 3.5% spread as the 1990s tech boom unwound, the more than 7% spread at the height of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the near 4% spread at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to data from Bloomberg and GAM.

Talk of a polycrisis in financial news circles may abound today but as far as the investment grade credit markets are concerned, we are in a golden age of low borrowing costs.

Chart 2: No end of low borrowing costs for investment grade

Source: Bloomberg

King cash on hand

The very largest corporations are enjoying another privilege, this time a function of their huge cash reserves.

With the six-month US Treasury bill earning a cool 5.2%, megacap firms with large cash hoards are accruing huge windfalls for effectively doing nothing.

Berkshire Hathaway has already been mentioned, and in theory if its entire cash balance was placed in said bills, they would be growing at a staggering $8.7bn clip each year. This would certainly take the sting out of the frustration of not finding anything to buy.

Looking at the so-called ‘magnificent seven’ stocks, their average cash balance was fully $48bn higher than the average cash balance for the S&P 500 as a whole.

Alphabet alone enjoyed an enormous cash pile of $110.9bn by the end of 2023.

If it was entirely invested in short-term deposit rates or bills, no less than $5.8bn would be the reward after 12 months, assuming no change in interest rates.

Unsurprising then that the market is punishing these firms less amid traditional ‘bads’ like sticky inflation and wars.

Credit climate changed

For smaller firms, the opposite sadly holds true. Saddled with the traditional banks for lending – just as in Europe – and generally offered variable, rather than fixed-rate borrowing, smaller firms are more vulnerable to high rates generally but have also suffered disproportionately as expectations for interest rate cuts have tempered over the course of the last few months.

At the start of the year the swaps market predicted fully three interest rate cuts from the Federal Reserve by the end of 2024. Now that prediction stands at barely one cut.

Headline inflation appears to have become inconveniently stuck at around the 3.5% level,1.5% north of the central bank’s official target.

Hence Fed Chair Jay Powell’s humiliating admission after May’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting that cuts would just have to wait for the time being, having been so confidently dovish at the end of 2023.

With some – admittedly on the fringes for now – commentators now even talking of outright rate hikes, the profitability of small caps just looks that much more vulnerable, rendering them a low-quality status which investors are avoiding amid simultaneous wars in Ukraine and the Middle East and a highly contentious upcoming US election.

This situation is a marked departure from the history of small caps from 1982 to 2020.

During that period, they were positively correlated with the ups and downs of the economy, as reflected in higher long-term market rates – bond yields.

As yields generally came down during this time amid a stagnating US economy and other esoteric pressures, small cap underperformance made a degree of sense.

But in the aftermath of the pandemic as the US economy recovered and bond yields accordingly picked up, small caps should have had their day in the sun.

Instead, the unique set of funding circumstances described meant that they were left in the shade.

Hefty rate cuts needed to ease the squeeze on small caps

It is not unreasonable for financial commentators today to question sticking with large caps, particularly given that the S&P 500 is up nearly 50% from 10 October 2022 to 6 May 2024.

But even amid such startling statistics, portfolio positioning always needs to consider how a given market’s underlying dynamics are evolving.

In the case of large caps versus small, it would appear that the fundamentals have shifted still further in the former’s favour even after more than forty years of outperformance and now-stretched valuations, while the prospects for smaller caps seem only to have dimmed.

Only meaningful lower discount and long-term rates could level the playing field at this point.

But with the US economy virtually booming and inflation seemingly stuck where it is, this seems a long way off. For now therefore, big remains beautiful.

Julian Howard is lead investment director, multi-asset solutions, at GAM