Over the past years, sustainability considerations have permeated the investing space. While traditionally used to reduce risk, ESG investing has evolved to consider not only exclusion-based approaches but also many different areas of sustainability and strategies for translating them into portfolio construction.

With almost 90% of global emissions covered by net-zero targets, a growing number of investors are also looking to focus their investments specifically on climate. Over the past three years, this trend has been underlined by significant inflows into climate-related ETFs as they received a quarter of total ESG UCITS inflows.

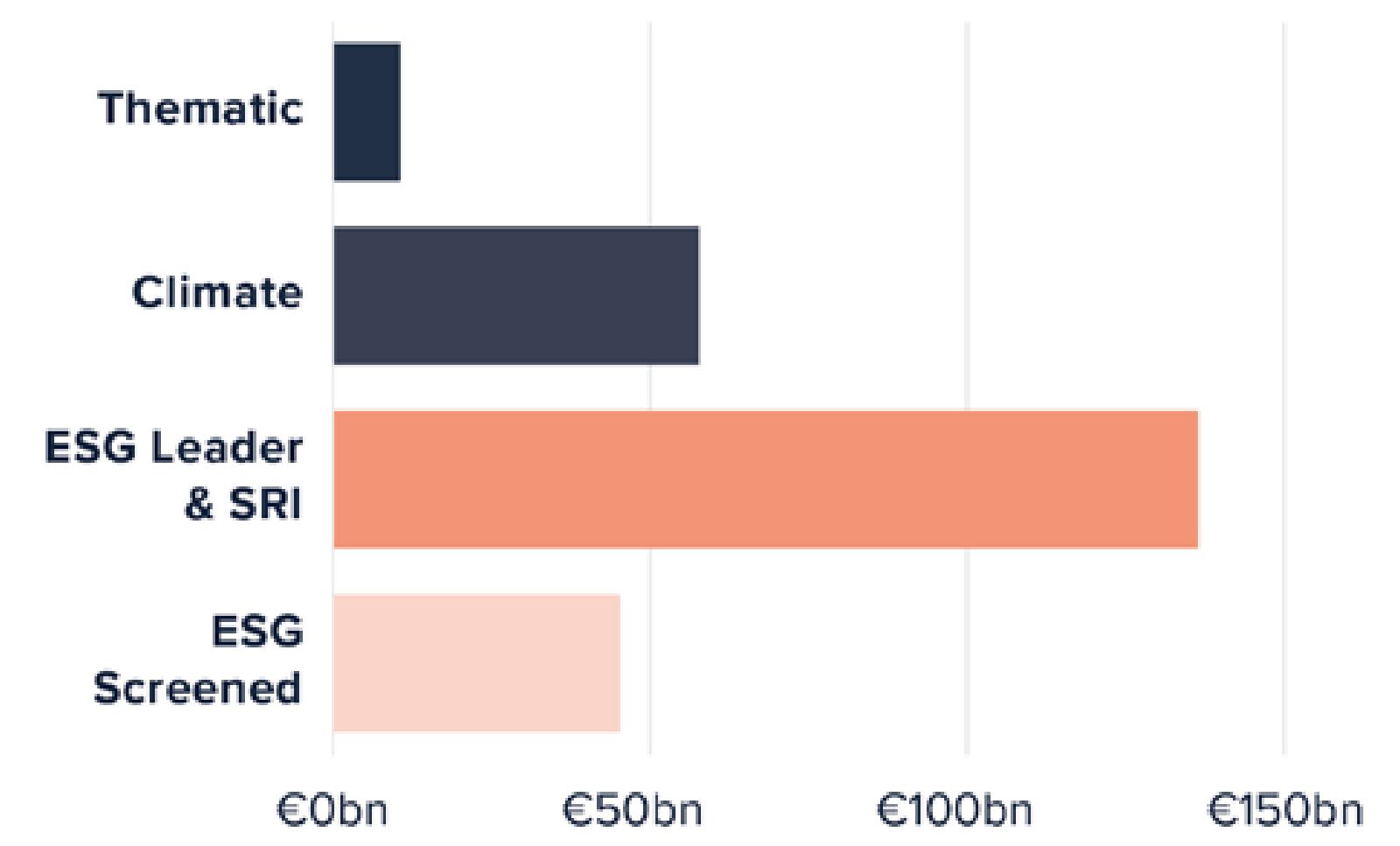

Figure 1: ESG UCITS ETF assets under management

Source: DWS International GmbH, as of March 2023. ESG Screened describes exclusion-based strategies with active share around 10%, while ESG Leader & SRI approaches follow stricter exclusions and only invest in companies with the best ESG scores in defined areas. Climate products focus on the climate transition and may replicate a regulated Paris-aligned or Climate Transition Benchmark. Thematic funds often focus on certain societal or economic trends, such as emerging technologies

Investors may have many motivations for turning to ESG and climate investing in particular, of which risk, regulation and the rise of investor-specific climate targets may be the most salient. The risk reduction argument has been broadened to include physical or transition risks arising from companies’ (poor) management of climate risks.

Regulatory requirements have for the first time provided clarity on specific investments – with the Delegated Act on Paris-aligned (PAB) and Climate Transition Benchmarks (CTB), the European Union has provided a clear framework on what such benchmarks must achieve.

In addition, a growing number of institutional investors have set decarbonisation targets for their assets, requiring portfolios to deliver a hard carbon reduction path. Given the different motivations, investors may turn to different investment strategies.

The well-known SRI approach is one way to achieve risk reduction through divestment, while pathway strategies can be more inclusive and green bonds offer the opportunity to directly reallocate capital to projects with an environmental focus such as the provision of renewable energy.

When discussing ESG investing in general, the ethical aspect should of course not be overlooked. After all, many exclusions are based on a consensus that certain activities are controversial and that one should not profit from them. The next step would be to ask how investors can influence the real economy and the companies they invest in (or divest from). This is especially true when it comes to climate investments and the associated race to the bottom in portfolio emissions.

We need to ask what role such investments can play in the climate transition – how can reducing carbon emissions at the investment portfolio level (or, to put it bluntly, ‘on-paper’ decarbonisation) support tangible, real-world decarbonisation outcomes? Reducing portfolio emissions is straightforward. For example, simply excluding around 3% of the weight of the MSCI ACWI IMI can reduce index emissions by 50%. Similarly, strict exclusion-based methodologies, such as the SRI standard, often achieve significant decarbonisation relative to their benchmark, accompanied by notable improvements in other ESG metrics.

In this sense, investors can influence asset prices and ultimately the cost of capital for divested companies.

From a financial perspective, the “law of large numbers” suggests that a sufficiently large withdrawal of investor funds should increase the true cost of funding because of the resultant reduction of equity values.

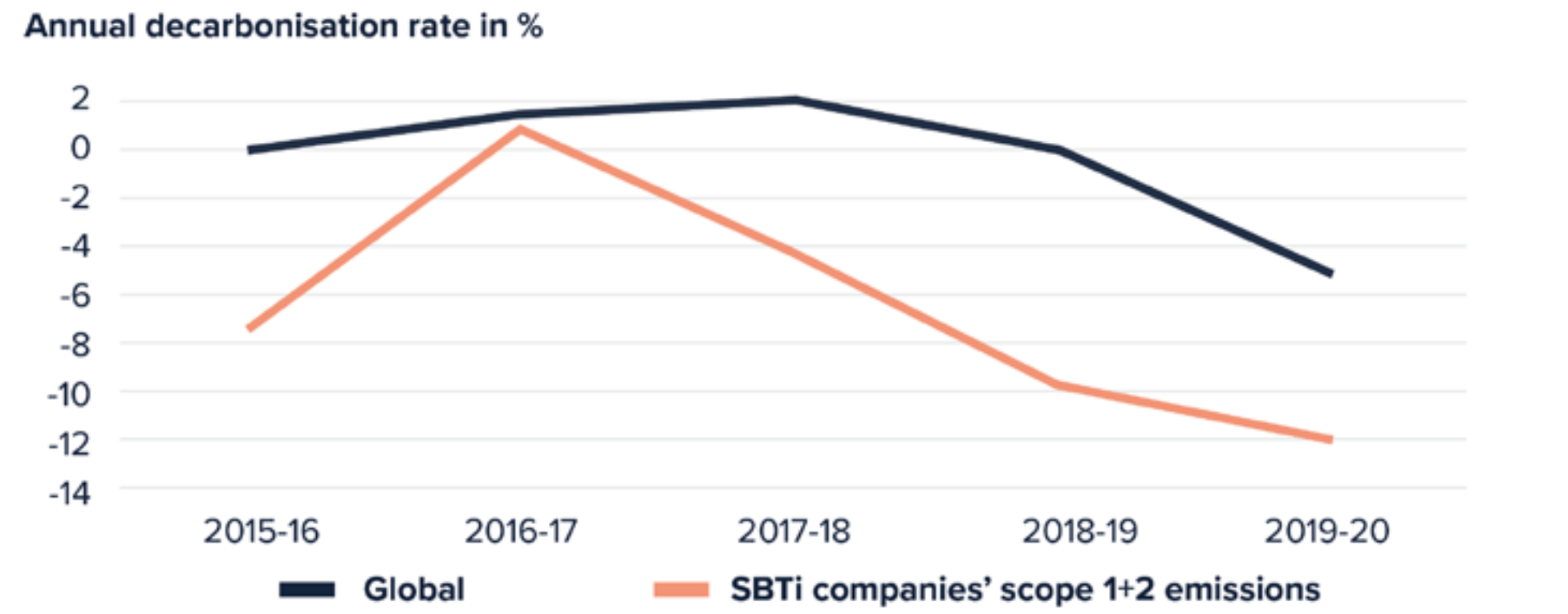

Consequently, this should also act as an incentive to improve ESG metrics – and may provide an opportunity to link decarbonisation at the portfolio level and in the real world: evidence suggests that companies with approved science-based targets (SBTs) are outperforming the broader economy in their decarbonisation.

Figure 2: Gross scope 1+2 emissions’ change rate of companies with approved targets vs the global economy

Source: Science-based Targets Initiative (SBTi) Progress Report 2021.

This provides a compelling case for incorporating SBTs as a variable in portfolio construction. Such an approach can benefit the investor and society at large: The investor has some confidence in the stability of their portfolio and potentially reduced future turnover due to changes in corporate climate metrics.

In addition, from a financial perspective, companies that have validated their 1.5°C target have seen an increase in their economic P/E ratio compared to companies with less ambitious or no targets. From a societal perspective, companies that have set SBTs have an obligation to pursue them and report transparently on their progress in real-world decarbonisation.

However, the cost of capital effect also reveals a conundrum in ESG investing: The portfolio that looks the most impressive in terms of ESG performance may only make a real difference over a relatively long time horizon. Fortunately, investors have additional levers at their disposal to contribute to positive sustainability outcomes.

According to the EU, in order to remain representative of the real economy, an equity PAB portfolio must not reduce its overall exposure to sectors with a particularly high contribution to climate change, the so-called high climate impact sectors. By maintaining exposure to these activities, investors can use stewardship and engagement to drive change.

The most direct way for public market investors to support the climate transition may however lie in the fixed income space, which is often overlooked due its less clear route of engagement. Green bonds are a uniquely positioned instrument to help (re-)finance transitional activities and support the development of new technological solutions in the short-term – an immediate lever that is often elusive in the realm of liquid equity markets. Nonetheless, one should not jump to the conclusion that only investments with a direct way of supporting green projects are appropriate climate investments.

Different investor goals warrant different strategies and in climate investing, it is important that investors seek dialogue through engagement as well as phase out investments in activities that cannot have a long-term place in a net-zero future.

Frederike Bauer is Xtrackers product specialist at DWS

This article was first published in ESG Unlocked: Is it time to draw the curtain on 'ESG'?, an ETF Stream report. To read the full report, click here.

This is a marketing communication. The value of an investment and any income from it can go down as well as up. Investments are subject to various risks, including market fluctuations, regulatory change, counterparty risk, possible delays in repayment and loss of income and principal invested. Without limitation, this information does not constitute an offer, an invitation to offer or a recommendation to enter into any transaction. No representation or warranty is made by DWS Group GmbH & Co. KGaA and/or its affiliates as to the reasonableness or completeness of forward-looking statements or to any other financial information contained herein. Due to various risks, uncertainties and assumptions made in our analysis, actual events or results or the actual performance of the markets covered may differ materially from those described. No assurance can be given that any forecast, target or opinion will materialise. © 2023 DWS International GmbH.

For Investors in UK: Issued in the UK by DWS Investments UK Limited which is authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority. © 2023 DWS Investments UK Limited As of 24/5/2023 | CRC: 096080