The European Parliament took the contentious step in July of voting to include nuclear energy within its taxonomy of sustainable activities, however, it remains to be seen whether other ESG frameworks will follow suit and if any naysayer investors will be swayed by the regulator’s decision.

Almost three years after first being discussed, nuclear energy, along with natural gas, look set to be added to the EU’s taxonomy via the Complementary Climate Delegated Act from 1 January 2023, earmarking them as sustainable investments for the time being.

The road to this verdict was not only meandering but full of obstacles, with Kenneth Lamont, senior research analyst at Morningstar, previously describing nuclear as being “stony on a political level” for investors and policymakers.

It began with the European Commission’s Technical Expert Group publishing the Taxonomy Technical Report in March 2020, which notably snubbed nuclear from its list of green activities.

A year later, leaders of seven EU member states wrote a letter calling on the European Commission to accommodate all paths to climate neutrality while the Commission’s Joint Research Centre argued nuclear should be eligible for ESG investment.

Even though the Commission announced a month later it would bootstrap nuclear and gas to its taxonomy via a Delegated Act, in October, a ‘Nuclear Alliance’ of 15 European Ministers called for the energy source to be included in the main body of the taxonomy by the end of 2021.

Ignoring these calls, the Commission published a draft of the Delegated Act on 31 December, which was soon met by fierce opposition as Austria and Luxembourg threatened to bring a lawsuit before the European Court of Justice.

Despite members of the Environment and Economic Affairs committees later voting against the proposed taxonomy changes in June, the defeat of the motion to block the Delegated Act in the European Parliament in July means nuclear will soon make its delayed entry into the taxonomy.

Conditional inclusion

While the move is significant for challenging the nuclear exclusions applied to many ESG frameworks and products, it bears remembering the Commission’s Platform on Sustainable Finance views nuclear as an ‘amber’ rather than ‘green’ activity – and its inclusion in the taxonomy is both conditional and time-limited.

The logic behind adding nuclear to the taxonomy, at least for now, is simple: it is a low-carbon source that can provide baseload energy and capacity is falling across the western world.

According to a recent paper by Société Générale citing data from The French Institute for Ecological Transition, nuclear produces six grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt hour of electricity versus 10 for wind and hydro and 32 for biomass.

Over its life cycle, nuclear produces 29 grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt hour of electricity, above the 26 grams for wind and solar but far below the 45, 75 and 78 grams produced by biomass, hydro and geothermal energy, respectively, according to a paper by the Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews.

Despite nuclear’s seemingly low-carbon credentials, the European countries most active in building new plants – Ukraine, the UK and France – currently only have a combined five plants under construction versus 17 for China alone.

Similarly, 27 out of the 31 reactors that have been under construction since 2017 are of Russian or Chinese design, according to analysis by SocGen.

The International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050 report argues nuclear capacity needs to double by 2050 to meet climate targets. If this is accurate, the Delegated Act makes sense if Europe is going to do its part towards net-zero goals.

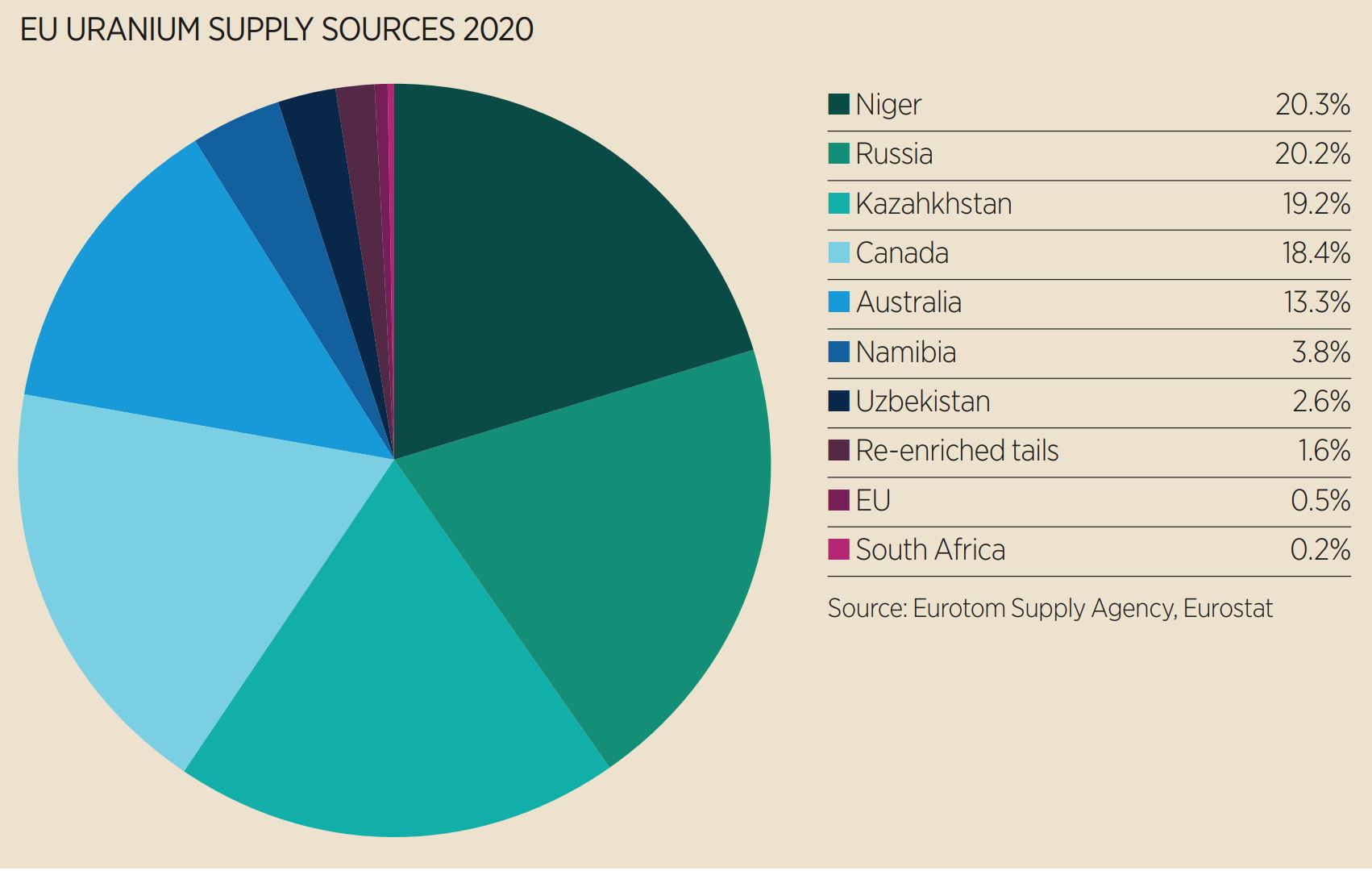

However, there are several compelling arguments against nuclear being in the taxonomy such as what to do with thousands of tonnes of radioactive waste, concerns around directing capital away from renewables and the worthwhile geopolitical point that in 2020, 20.2% of the EU’s uranium supply came from Russia and 19.2% from its ally, Kazakhstan, according to Eurostat.

It is also worth noting the size of political opposition to nuclear as a ‘transition energy’, with 278 of 639 MEPs opposing the Delegated Act in July’s motion.

Considering these points, the Commission applies a number of screening and disclosure conditions to nuclear’s taxonomy inclusion. For instance, there are screens based on scientific advice such as requiring disposal facilities for low-level radioactive waste to already be operational, member states having a plan for high-level waste disposal by 2050 and a ban on exporting radioactive waste to developing countries for disposal.

Also, large listed non-financial and financial companies will be required to disclose what portion of their activities are linked to the energies included in the Delegated Act.

Greater complexity across EU policy

To remain consistent, the EU will have to bring its other ESG frameworks in line with these new disclosures, adding to an already challenging list of requirements for companies being asked to become more granular in their reporting.

According to the law firm CMS, the Commission has asked the European Supervisory Authorities (ESA) to suggest changes to how companies disclose on fossil fuel and nuclear activities in pre-contractual documents, websites and periodic reports under the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), by 30 September at the latest.

CMS said: “Ultimately, this would mean more granular quantitative reporting than the current SFDR Level 2 – coming into force from January 2023 – which only requires specification of EU taxonomy-aligned investments versus non-EU taxonomy-aligned investments, with no deep dive into specific sectors or sub-sectors.”

While highly conditional and potentially rushed, such measures will have the practical impact of reflecting taxonomy changes into new nuclear subsectors eligible for inclusion in SFDR Article 8 and 9 products. Supporting alignment on nuclear across ESG frameworks,

Rob Edwards, director of product management, ESG indices, at Morningstar, told ETF Stream: “There are pieces of the puzzle that are fighting for the same outcome of making progress on climate and other issues but they are not always perfectly in sync with each other. I would like these standards to evolve so they are all speaking the same language and having equivalent standards.”

Natixis previously described Article 8 and 9 funds’ exposure to nuclear at the end of 2021 as “very low” at under 2% of $4.5trn total European assets in December 2021, according to data from Morningstar.

As nuclear starts getting treated more favourably, the challenge will then become deciding how to segment different parts of the value chain.

For now, Europe’s two uranium ETFs are categorised under Article 6 of the SFDR – meaning they are not viewed as sustainable. Meanwhile, the iShares Global Clean Energy UCITS ETF (INRG) is categorised under the ‘dark green’ Article 9 while allocating to utilities firms engaged in nuclear such as Brazil’s Minas Gerais.

Europe’s two electric vehicle battery ETFs are also categorised under the ‘light green’ Article 8 despite being as much as 37.8% exposed to companies mining for cobalt, lithium and other metals. It would be interesting to see how a broad nuclear value chain play would be categorised under SFDR.

Index providers not feeling the buzz

The ultimate test, however, will be if taxonomy inclusion changes investor attitudes towards nuclear, given its aim is to act as a framework for guiding capital towards worthy recipients. Joachim Klement, investment strategist at Liberum, said it is possible index providers offering Paris-Aligned Benchmark (PAB) products – based on the taxonomy – will become more lenient.

“Many index providers will remove nuclear power operators from their exclusion lists and will become more flexible in including utilities that generate power from nuclear facilities in their indices,” he added.

However, he warned others with their own internal rules and those fulfilling client mandates would be less likely to change their indices in fear of losing business.

FTSE Russell, for instance, continues to categorise nuclear as tier three under its Green Revenues Classification System, meaning it has some environmental benefit but this is overall net neutral or negative.

The index provider said in a statement there are around 30 green taxonomies under development – and for now, it wants to see more disclosure of green and non-green revenues by companies to improve the accuracy of taxonomy judgements.

Others such as Morningstar and Solactive do not expect the taxonomy change to have an immediate impact, given what they described as an increased focus on customisation within ESG, based on the needs of different of end clients.

“Clients in different countries are likely to have different sets of exclusions and institutional clients will already have their own policy set in terms of exclusions and lists set up by their ESG or sustainability board,” Edwards continued. “The taxonomy made it a little easier to have the conversation about nuclear but ultimately things are just getting a lot more customised. When we are working with clients, a lot of time they are already going to have an opinion.”

Timo Pfeiffer, chief markets officer at Solactive, agreed regional and institutional differences will remain and so far, his firm’s ESG business has been “unaffected”.

Looking ahead, Pfeiffer forecasted the taxonomy change will create a “more elaborate and distinct decision-making process” around whether to include nuclear in ESG products but it is likely future taxonomy-compliant indices will be constructed both with and without nuclear.

Edwards said his team “did not hear the taxonomy news and get a flood of emails from clients”. Also, as with the introduction of the PABs and Climate Transition Benchmarks (CTB), taking a new ESG framework from idea stage to implementation and then common adoption takes years.

“It will be a slower moving process if something does happen,” Edwards argued. “Details like this do come into play but setting standards does not happen quickly. Broad ESG indices are very different to what they were three years ago but this evolution takes time.”

Some investors might also be put off by the fact the technical screening criteria of the Delegated Act will be reviewed every three years, which includes time limits for the contribution of nuclear and gas to climate change mitigation efforts. If the EU reverses its recent taxonomy changes in future, investors in nuclear and gas will have to rush to get rid of these exposures in order to remain aligned.

For now, ESG might like nuclear a little more than it did a year ago but EU taxonomy support only applies to certain subsectors, subject to conditions and set to be reviewed over time.

Overall, though, the Delegated Act should be understood as more an act of EU pragmatism than moral change of heart on what it means to be sustainable. Nuclear may have a role to play in net-zero efforts but will face an uphill battle to convert its detractors.

This article first appeared in ETF Insider, ETF Stream's monthly ETF magazine for professional investors in Europe. To access the full issue, click here.

Related articles