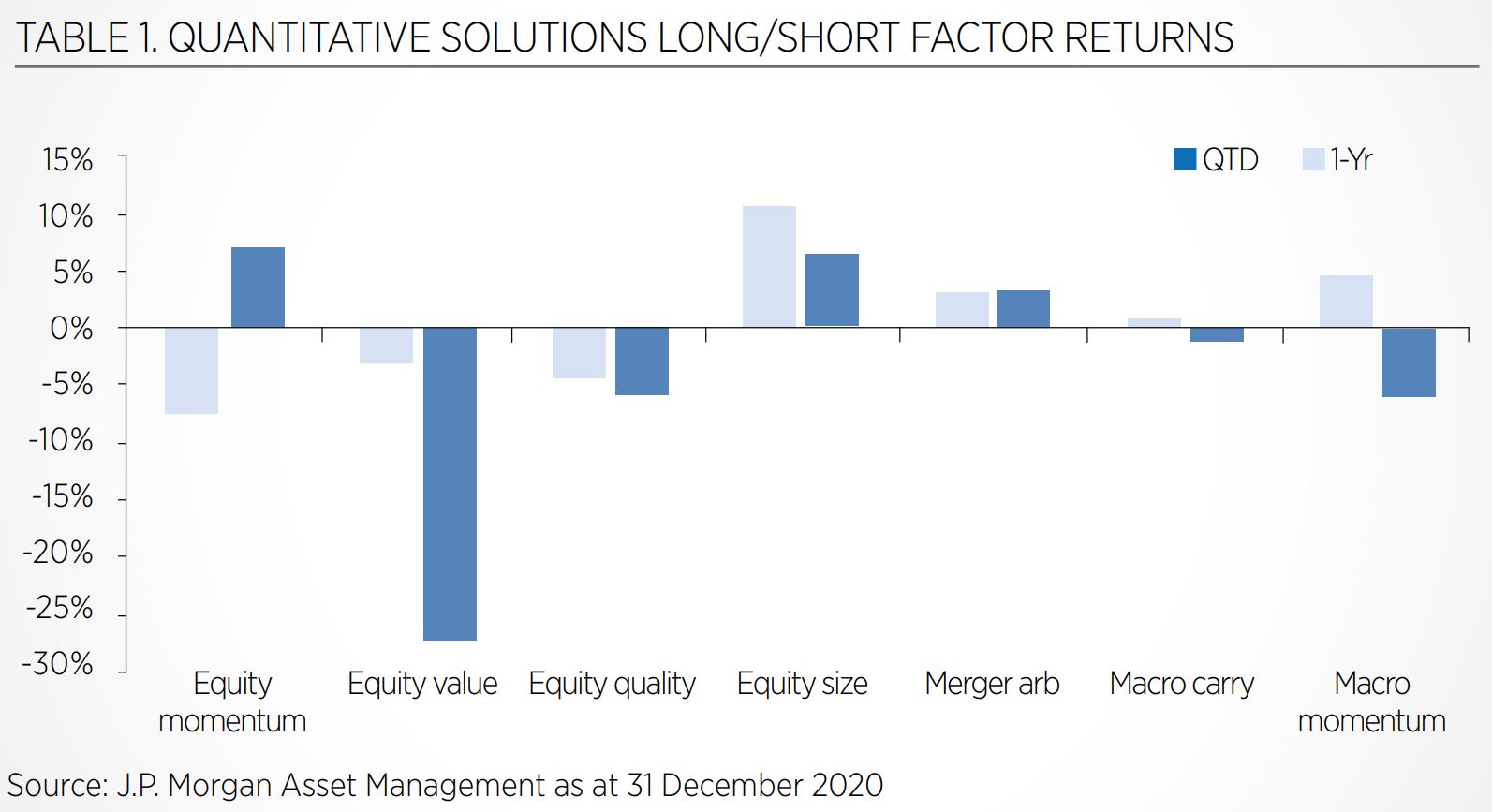

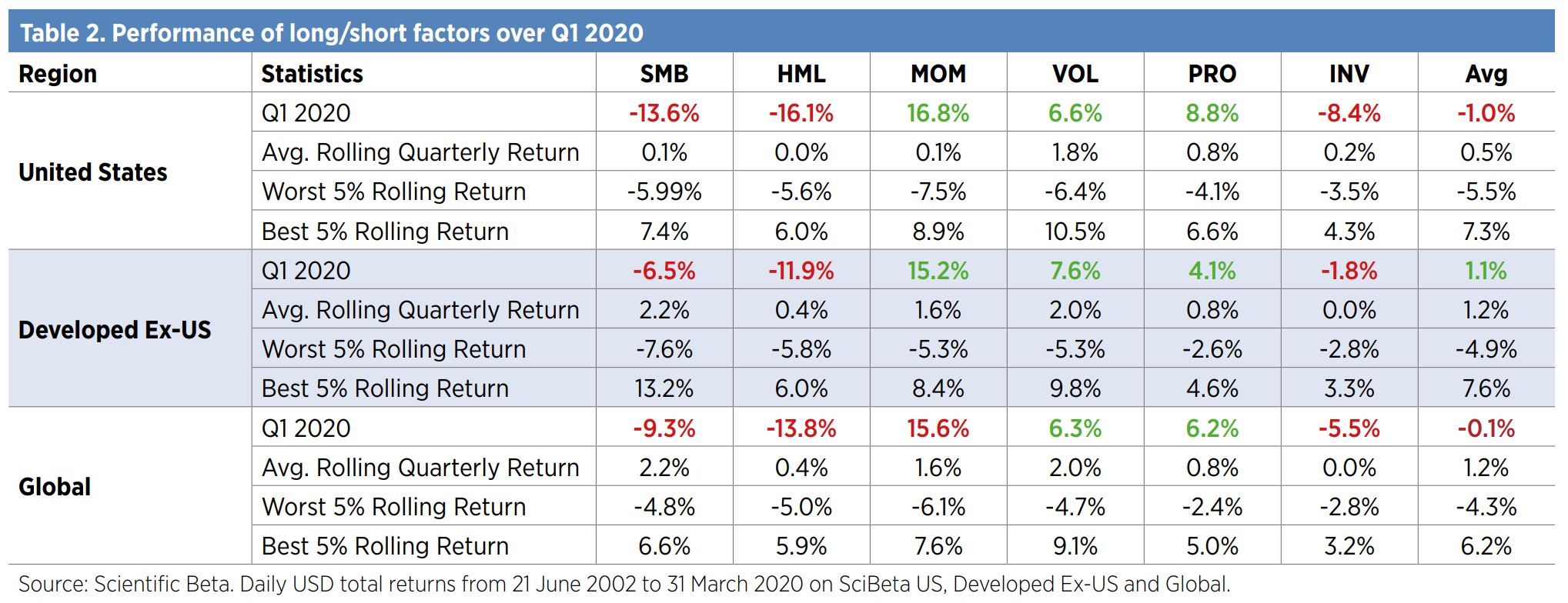

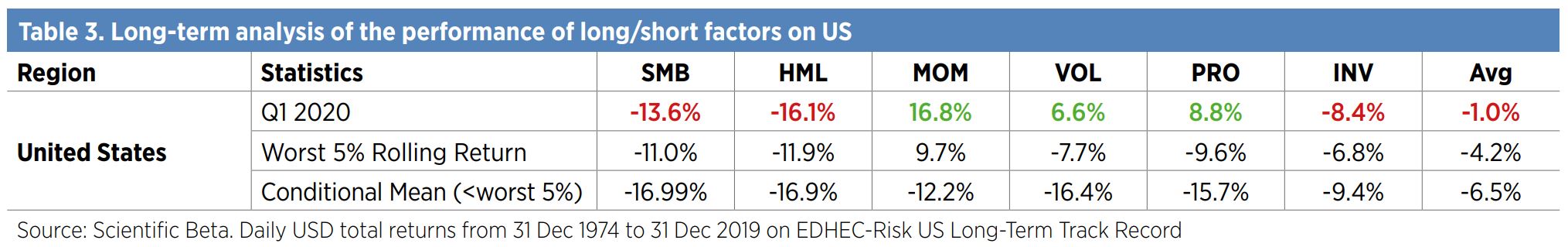

Much has been written about the underperformance of multi-factor strategies during 2020, with much of the blame being attributed to the value factor, which experienced particularly strong underperformance as a result of the coronavirus pandemic last March. In fact, the value factor experienced its worst drawdown in 30 years, according to JP Morgan Asset Management, finishing 2020 with its worst calendar year return in the history of the firm’s data.

As a result, the question of whether factor timing works in practice has cropped up once again, and opinions on the subject differ. For some, like Eric Shirbini, global product specialist at ERI Scientific Beta, the answer is a resounding ‘no’, while others are more optimistic about the potential benefits of timing factors. As Shirbini said: “Factors are related to risk premia and who can time that? It is very difficult to predict and respond to changing macro-economic conditions. The only sensible solution is to invest in a portfolio of factors with equal exposure to each.”

Vitali Kalesnik, director of research for Europe at Research Affiliates, on the other hand, said successful factor timing is theoretically possible, based on research the firm has conducted: “I believe yes, based on the evidence that we have found, factor return is predictable over time.”

However, all experts Beyond Beta spoke to agree that successfully timing factors is extremely difficult. While the strategy may work on paper, in reality, it is difficult to create enough “breadth” in a portfolio that is seeking to time factors, since there are not that many factors to choose from, Kalesnik said.

“You cannot diversify factor timing bets around that many factors,” he continued. “This translates into a poor information ratio and as a standalone signal it does not allow the investor to benefit all that much in terms of gain per unit of risk.”

The other downside is that factor-timing strategies can incur high transaction costs, especially when it comes to investing in the momentum factor, which requires high portfolio turnover. This “puts a limit on how aggressively you can benefit” from a momentum strategy, though Kalesnik noted that “adding a little bit of [momentum] will improve the overall information ratio, if you do not trade too much”. He added, however, that this is “just one of the tools in an investor’s portfolio, so do not expect it to do wonders”.

There are two main techniques for timing factors. One is based on valuations, the idea being to buy companies with the lowest P/E ratios relative to history or to the market average. The other is buying factors based on price momentum, which involves buying assets that have performed well in the recent past and selling them when the returns are deemed to have peaked in an effort to take advantage of market volatility.

However, Shirbini noted that using either of these strategies means an investor is no longer factor-timing, as employing these techniques automatically creates exposure to either the value or momentum factor. For example, “if you try to buy the momentum factor when it is cheap, then all you are doing is buying momentum when it overlaps with value” and so on.

Part of the issue also lies in the difficulty of constructing factors, Tatjana Puhan, deputy CIO at TOBAM, said. “When you have huge dispersion of factor returns, having construction issues might very badly backfire on you,” she stressed. “This is what happened in 2020 to many multi-factor portfolios that were heavily exposed to value, for example.”

When trying to construct, say, a value factor, the first question would be to decide what “the right proxy for value” is, Puhan said. Then, the challenge is to turn this into “an actionable factor”. Given the breadth of different ways to measure value, the outcome in terms of performance could be “very positive or very negative” – and not necessarily predictable.

The other obstacle is the difficulty in predicting the macro environment – political risks, policy changes, idiosyncratic risks – which all feed into how well one single factor will perform in a particular environment. In addition, Puhan believes there is “a lot of data mining going on to show that the timing model works,” when in reality any outperformance tends to be inconsistent.

Altaf Kassam, EMEA head of investment strategy and research at State Street Global Advisors, agreed: “You can go back through history and back-test for decades and you get some really nice-looking results as a lot of the noise gets cancelled out. But if you try to apply these results over the next week, month, quarter, it turns out the noise swamps out any signals.”

Balanced approach

Kassam’s advice for investors that do not have a strong view on any one factor is to hold a combination of factors, since exposure to a single factor naturally means exposure to more risk.

However, this also means investors are likely to have to be patient and wait longer for outperformance to materialise. For those clients that already have a specific factor tilt in a portfolio, a better option might be to find complementary exposures that would balance out the risks.

In Shirbini’s view, the best way to invest in factors is to create a “well-diversified factor strategy”, which involves minimising stock-specific risks using a combination of equal weighting, equal risk contribution to each stock, and reducing correlations between holdings. This is the approach Scientific Beta takes to constructing multi-factor indices.

TOBAM is also an advocate of diversification and uses a maximum diversification approach to construct its Anti-Benchmark portfolios, which aim to maximise the number of sources of risk to which they are exposed. “We do not know what the future will bring – in that sense, we are the least insightful manager you can find,” Puhan said.

However, Kalesnik argued that even though factor timing is difficult, investors can still look to time risks by “nudging” their weights in favour of factors with “good signals” and reducing exposure to negative signals throughout the cycle.

“At times when volatility is high, it is best to reduce your factor exposure, as that alpha is likely to come at a higher risk,” he explained. “During times of low volatility, on the other hand, alpha comes at a lower relative risk. In addition, factors can go down much more than investors expect, and they tend to go down together. When these risks appear and investors start to see more correlation [between factors], it is better to reduce factor exposure and tilt towards cap weighting.”

This article first appeared in the Q1 2021 edition of Beyond Beta, the world’s only factor investing publication. To receive a full copy,click here.